The perennial borders in Bunny Williams’ garden change colors with the seasons. Late spring is a symphony of blues and purples.

Portrait by Miguel Flores-Vianna, Courtesy of Bunny Williams

When Bunny Williams pulled into the drive of a mid-19th-century Connecticut farmhouse, “I could feel that there was something special about the house,” she recalls. “It was in absolutely terrible condition, but it had a quirky personality, with double lattice porches on it and a wonderful, rambling quality.” She knew instantly that she’d found her way home. What she certainly didn’t find was any kind of garden. “I couldn’t even walk more than ten yards for all the overgrown weeds and brambles,” she says. For Williams, however, that was far from a deterrent. Although the designer is renowned for creating refined interiors that exude graciousness and comfort, she’s not afraid to get her hands dirty, particularly when it comes to matters of the garden.

Williams set about a meticulous renovation, decoration, and at times, virtually start-from-scratch creation of every space, a process she recounts with her warm, down-to-earth manner in the book, An Affair with a House (Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 2005). But it could have just as easily been titled An Affair with a Garden, for the designer’s perspective is that there really is no distinction between the two. “I think about a garden exactly the way I think about a house,” she says. “The biggest mistake people make is not connecting the house to the garden. You have to enter it; create ways to move through it; think about a color palette that appeals to you; and design outdoor rooms that will reflect your lifestyle, whether that means a vegetable garden, flower beds, or pots of annuals.”

The sunken garden was the first outdoor project that Williams tackled.

Although there was no question the property needed immediate attention, the beginning stages were very much about simply cleaning up the land—trimming the trees, clearing things out, and getting the grass under control—tasks that consumed almost every waking hour of the weekends. “I needed to create a canvas so I could begin to see where I wanted things,” says Williams. “I believe the key to starting a garden is getting to know the landscape. The land will always tell you what to do.”

The first area to speak was what would eventually become the sunken garden, where the yard gently slopes down to a flat and wide expanse of lawn. It’s a garden that has matured over the course of 30 years, and its owner has honed her gardening knowledge along with it.

“I made a lot of errors from the start,” says the designer, “including planting the perennial borders incorrectly and with flowers that didn’t provide proper impact. But one of the greatest things about gardening is that most mistakes are relatively easy to correct—you pick up, transplant things where they’ll work better, and move on.” To define the space, Williams enlisted a sculptor friend to create a low stone wall, and she later added a dark reflecting pool, framed by box hedges.

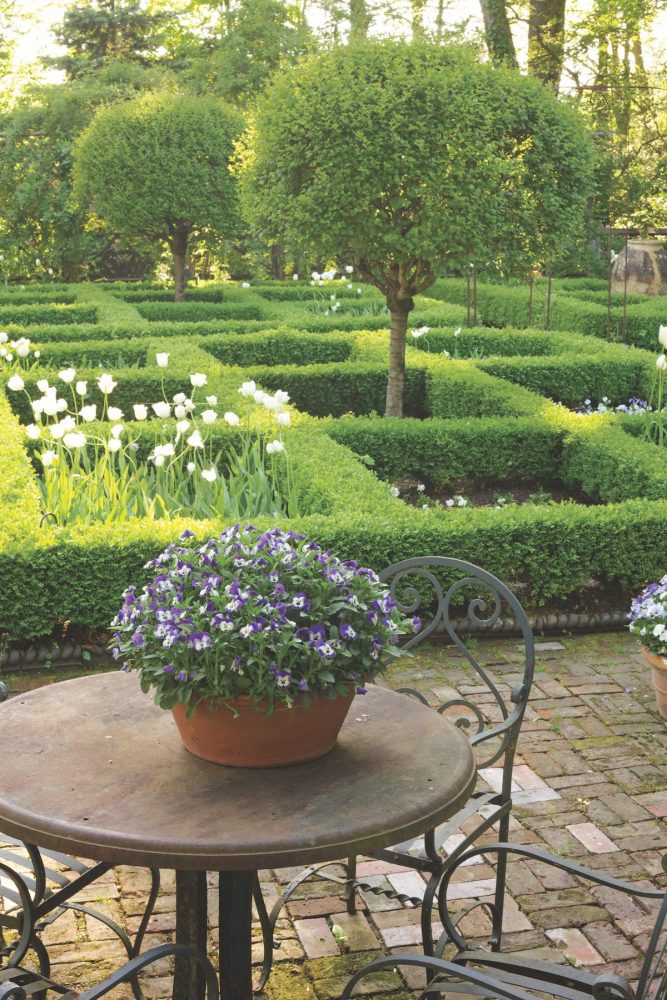

After dining in the conservatory, guests often wander through the green-and-white parterre garden, patterned after a design by legendary English gardener Rosemary Verey. Two Korean lilac trees anchor the space.

Other garden rooms would follow. Just as with a progression of rooms in one of Williams’ deftly designed houses, each garden transitions from one distinctive mood and function to another, but all guided by a sensibility that gives it a cohesive and appropriate sense of place. A parterre garden that started out as a potager (patterned after one designed by Rosemary Verey in the Cotswolds) eventually morphed into a more formal green-and-white garden, when the adjacent barn and conservatory were renovated into spaces to gather and entertain friends.

Stone steps and arborvitae lead to the woodland garden, where an antique urn serves as an architectural focal point.

In the shady, woodland garden, a path skirts through carpets of ferns, primulas, and spring bulbs, and winds around a man-made pond that looks as if it has been placed just so by Mother Nature, rather than by a designer’s whim. Cutting and vegetable gardens yield a bounty of materials for Williams to make fresh floral arrangements for the house, and for her husband, John Rosselli, to use to in the meals he expertly whips up in the kitchen. “It’s the variety in all these outdoor spaces that keeps things interesting,” Williams says. “I definitely didn’t want ‘Versailles,’ with acres and acres of manicured gardens. I like having different experiences throughout the landscape.”

The pool house is Williams’ rustic ode to a classic Greek temple.

One of the more recent projects has also become somewhat of a calling card for the property and the surrounding town of Falls Village. “When John and I decided to build a swimming pool, I wanted to site it away from the house, because I didn’t want to look at it all through the winter,” says Williams. Rosselli identified a prime location, up on a hill of to the side of the house, but that meant they would also need a pool house for convenience. “I thought the hillside called out for something classical, and our town is filled with Greek Revival architecture. So why not have something reminiscent of a Greek temple?”

The pool house terrace, framed by weathered oak columns, becomes a favorite spot for entertaining and lounging during warm months. The woodland garden lies just beyond.

Williams consulted with architect Gil Schafer on the historic, mathematical proportions of such a temple, and then the team set about putting their own stamp to make it truly appropriate for the setting. “I wanted to make it look like the woodland garden, which is just beyond, had extended out and somehow created this building,” Williams says. “My wonderful carpenter, Gerald McMahon, found white oak trees with trunks all the same size and width, and wrapped them after he cut them down so we could protect the bark while they were being transported to the site.” Those trees would become rusticated versions of Greek columns. For a clever finishing touch, Williams used pinecones to fill in the pediment. The result has become not only an architectural landmark, but also an oft-used space to entertain casually in summer.

Even the property’s service area, with a utility barn inspired by a 19th-century carriage house, is picturesque.

Although at this point Williams has no major plans for breaking additional ground—perhaps it’s time, after three decades of plotting, planning, and planting, to relax and just enjoy it all—she acknowledges that a garden is never really finished. “Yes, you do have to know when to stop, and we have enough to handle,” she says. “Our focus now is just to keep improving what is there.”

But as with all endeavors Williams undertakes, she never wants to stop learning and growing, and the land is a willing, if sometimes unpredictable, teacher. “A garden is always a lesson in complete humility,” she says with a laugh. “With the inside of a house, I can be in complete control—I can make the furniture the right size, manipulate colors to get exactly what I want. But I cannot, no matter how much I want to, control nature. It’s sort of a higher power that takes over. I’m still adjusting to that.”

When not in one of her gardens, the designer can often be found in her beloved country conservatory, setting the stage for one of the frequent dinner parties that she and husband John Rosselli give on weekends.

By Karen M. Carroll | Photography by Mick Hales

Note: Following this article’s publication in 2013, Williams’ garden continued to evolve. The photo below shows her sunken garden in 2019, which appeared in Flower‘s feature Casting a Spell with Pennoyer Newman.