Photo by David Dashiell

English, French, and Italian influences are evidenced in The Mount, Wharton’s home in Lenox, Massachusetts.

Born Edith Newbold Jones in 1862, Edith Wharton spent her childhood traveling around the world. When her family moved to Europe, she was exposed to grand gardens, flower-filled hillsides, piazzas, and ancient ruins. The beauty she observed made a lasting impression on Wharton, leading to her passion for literature, interiors, and nature. When her family returned to Pencraig, their home in Newport, Rhode Island, Wharton found even more inspiration in the landscape. In her memoir, she wrote, “The roomy and pleasant house of Pencraig was surrounded by a verandah wreathed in clematis and honeysuckle, and below it a lawn sloped to a deep daisied meadow . . .”

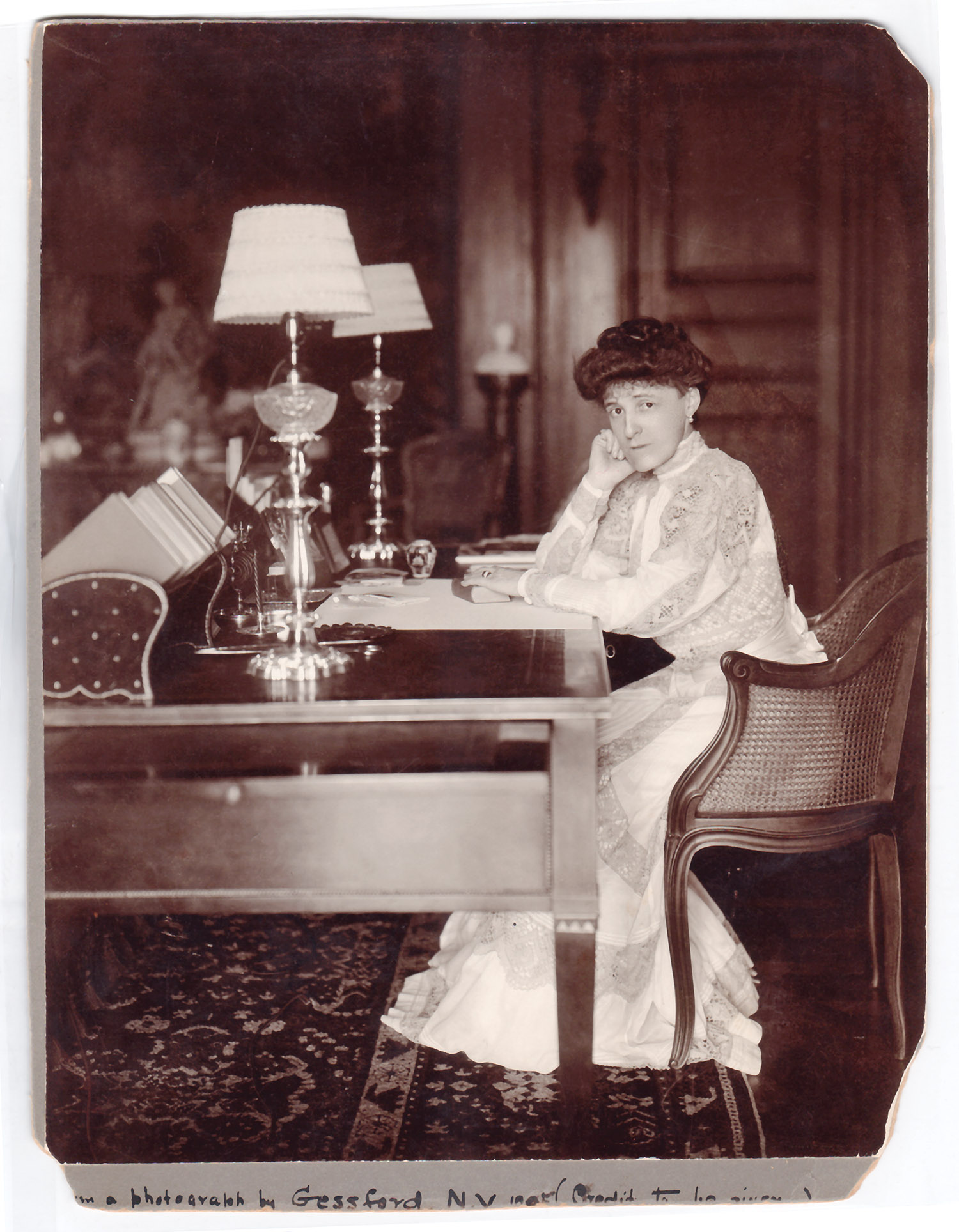

Photo courtesy of Charlotte Moss

Wharton in her library at The Mount. Her highly personal collection of books was repurchased by the Edith Wharton Restoration in 2005, adding to our knowledge of the woman, the author, and the designer.

Wharton made her social debut into New York society in the winter of 1879. Six years later, she married Edward Wharton, from a well-established Philadelphia family, and the couple settled on a property called The Mount in the Berkshires of Massachusetts. Wharton worked with architect Francis L.V. Hoppin to execute her vision for their new home. From the architecture to the interior design to the gardens, she incorporated her style, along with her collections from abroad. Using the influences from a lifetime of traveling Europe, she designed the beautiful gardens at The Mount.

In 1911, the couple sold The Mount and then divorced two years later. Wharton moved to France and eventually purchased the Pavillon Colombe in Saint-Brice-sous-Forêt in a suburb of Paris. Her study of architecture and gardens is evident throughout the property, specifically in the different garden “rooms.”

As one might expect, Wharton’s descriptions of the Italian gardens she visited are equal to the powerful pen that shaped her prolific writing career. Neither a garden book, nor a travel book, Italian Villas and Gardens takes readers on a walk from each villa through the gardens where she points out the transitions and then on the landscapes at large. In the opinion of English landscape historian John Dixon Hunt, “…that is the most exciting emphasis of her book.” However, there was one issue that frustrated Wharton with the book’s publication—the decision made by her publisher to have Maxfield Parrish as the illustrator. Parrish refused to visit the locations Wharton wrote about or to collaborate with her. He had his own ideas and created 26 illustrations that, while attractive on their own, were not the vision of the author.

Photo by David Dashiell

A view down the allée of pleached lindens, known as the Lime Walk, at The Mount. Wharton’s list of favorite flowers included delphiniums, dianthus, phlox, stock, and hydrangeas.

Photo by David Dashiell

Wharton’s curiosity is visible in all aspects of the gardens as she merged Italian and French influences with an American spirit. Here, an Adirondack-style bench Is perfectly at home in this rustic stone niche.

To fill in the gaps left by the absence of the illustrations she desired, Wharton used words that few are capable of summoning and committing to paper. The result is a guide through Villa Gamberaia, Isola Bella, Pisano, the Borghese Gardens, and more that many consider to be one of the greatest examples of garden writing. One such description reads, “It is safe to say that no one enters the grounds of the Villa Medici without being soothed and charmed by that garden magic which is the peculiar quality of some of the old Italian pleasances. It is not necessary to be a student of garden-architecture to feel the spell of quiet and serenity that falls on one at the very gateway.”

“The Italian garden does not exist for its flowers; its flowers exist for it: they are a late and infrequent adjunct to its beauties, a parenthetical grace counting only as one more touch in the general effect of enchantment.”

—Edith Wharton, Italian Villas and Gardens

For her own gardens, Wharton followed the three elements of garden design she outlined in her book: “marble, water, and perennial verdure.” Classical busts on pedestals peeped out from foliage-covered niches while stone urns overflowed with flowers. Stone paths with flower borders wound through the property, and her rose garden surrounded a pond covered in water lilies. Wharton once wrote to a friend: “I got your splendid tulip list, for which all gratitude, & am ordering from Van Tubergen. My new rose garden is promising, & I find this soil so decidedly made for rose growing that I mean to plant hundreds more this autumn, & to root up nearly all the old varieties. The new ones are so much more worthwhile, & one can now get varieties of every kind to which mildew is unknown.”

Photo courtesy of Charlotte Moss

Wharton surveying her garden at Castel Sainte-Claire du Chateau in Hyères, located high above the Mediterranean. The garden was lush with native plants, succulents, plumbagos, and bougainvilleas, all under the protection of eucalyptus and orange trees.

In 1927, Wharton purchased a villa in the hills above Hyères, France, where she lived during the winters and springs. She called it Castel Sainte-Claire du Chateau and filled the villa’s garden with cacti and subtropical plants. Wharton spent most of her time on the terrace enjoying the spectacular views of lawns bordered by flowers and shrubs and dotted by arched topiaries. She died 10 years later, leaving behind a layered legacy. The first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for literature, Wharton lives on in the subtle irony between the lines of her novels, in the soil at The Mount, and in the flowers at Castel Sainte-Claire du Chateau.

By Charlotte Moss | Photography by David Dashiell

With a lifelong love of gardening, designer Charlotte Moss has long been intrigued with what draws people—especially women—into the world of horticulture. She has a forthcoming book with Rizzoli on the subject of gardening women, set to release in 2026.