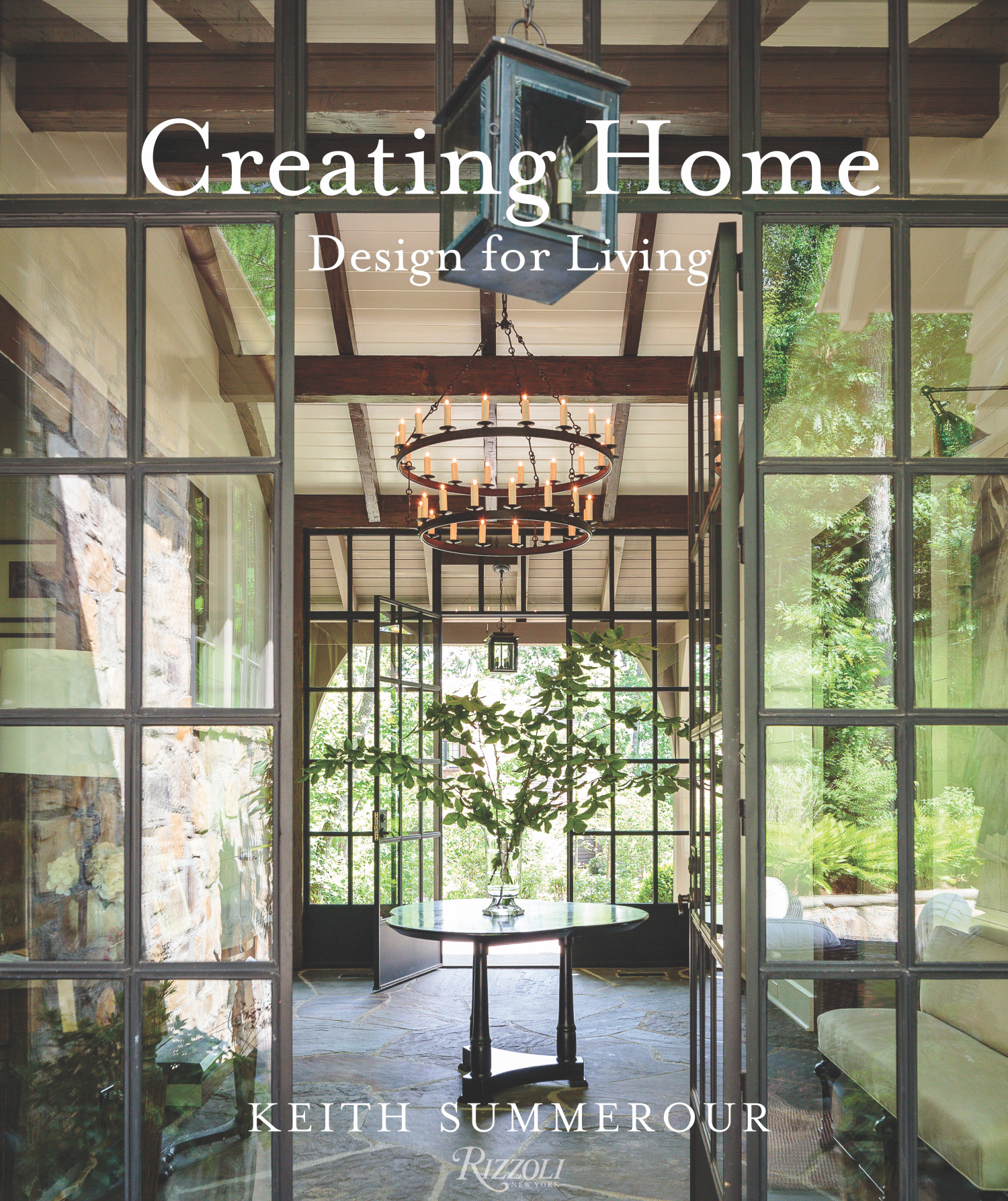

In his book, Creating Home (Rizzoli New York, 2017), Keith Summerour writes, “The porch represents the middle zone between the conditioned and the uncovered and permits us the exquisite pleasure of keeping one foot in comfort and the other in the wild.”

Q&A

Flower: Do you remember your “aha moment,” when you realized you wanted to spend your career designing beautiful houses?

Keith Summerour: It’s kind of a funny story. I went to Auburn University to run track. Bo Jackson was also on the team, and in my first race I came in dead last. My dad suggested that maybe I should give up the idea that I was going to be a professional athlete and find another direction. He recommended architecture, and Auburn has an excellent program, but in order to get in you need to have proof that you have some ability. My passion at that time was Star Wars, and in high school I had drawn a detailed plan of the Millennium Falcon. I showed that to the admissions department, and they said, “Great, you’re perfect. But you’ll need to get your grades up before you can get in.” So I did, and it was like a fish to water—I loved everything about architecture and have ever since.

Well, there’s certainly no shame in losing a race to Bo Jackson, and the architecture world is richer for it.

Architect Keith Summerour at work in the studio of his weekend house, a 70-foot stone tower he designed in rural Georgia.

your houses vary in their aesthetic, but always seem to be rooted in tradition. Would you describe yourself as primarily a classicist?

I’d be proud to have that as a medal, and if I could earn it, I’d wear it. But my view of classicism is very broad in that it doesn’t necessarily have to relate to the mathematical perfection of Greek temples, per se. In fact, some of the most lovely, classic buildings are the vernacular ones of the old South: cracker shacks, fishing cabins, and barns. For me those are still within the classical realm because they were built by hand and to human proportions. They are not refined, but that makes them even that much more interesting. I think of classicism like the keys on the piano. No one has ever found all the combinations and we never will. So I’m a classicist if someone buys into that. And if they buy into the idea of Greek temples and that type of perfection, well, I can do that, too.

A Norman-style house on Long Island Sound sits on the highest elevation of the property, and appears to undulate with the rolling landscape.

What other architectural styles do you inherently gravitate toward?

I’m always drawn to agrarian architecture. I was recently in Umbria, and the Italian farmhouses of that area speak to me, how they are nestled into hillsides and add to the character of their environment, rather than take away from it. Agrarian architecture anywhere in the world has similarities; it’s just clothed differently. In the South, it’s a wooden barn, whereas in Italy, it’s stone, or in France, it’s stone and wood. That ties into my strong belief that the materials of a house I’m building should be of the area whenever possible.

For a historic house in Atlanta, Summerour designed a new garden facade and collaborated with landscape architect John Howard on a garden plan that stays true to the house’s classical roots.

Could you talk more about the role the landscape plays in your design process, both the sense of place and the garden to come, as the creative team envisions it?

It always starts with the land, and a building should grow out of it organically rather than insert itself. I work from the garden to the house, not the other way around. Having a father who taught college botany, I grew up knowing both the Latin and common names for flora, but I didn’t think much about that until I worked with Ryan Gainey early in my career, doing drawings for him of garden designs, driveways, cottages, pools, anything relating to existing structures. That opened my eyes to the world of architecture beyond just creating a building, and I’ve never veered from that perspective.

Other than the land, what’s a frequent starting point when working with clients during the conceptual stage?

Ensuring that the house responds to the way that people really live versus the way people think they should live. Most people don’t entertain all that often. Clients will come into my office believing that a house should be about walking through the front door. And I’ll say, “Pull into your garage, and that’s where your house should begin.” That experience should be as special as when a guest arrives in the foyer. It gets them thinking, “This is for me. It isn’t for my three brothers and their families who come for a few days every other Christmas.” They get excited, and ultimately the house becomes more relevant.

We can design something perhaps smaller than what they originally thought, and really invest in the quality of materials. With some of my older clients who have grown children and grandchildren, I might say something like, “You take the money you save from not building such a grand house and put them up in the Ritz-Carlton every time they come in town. I guarantee you they’ll come back, and everyone will be happier.”

In this North Carolina mountain house, all the woodwork was crafted of white oak from the area, illustrating Summerour’s preference to use local materials whenever possible.

One of the most intriguing houses featured in the book is probably the most personal for you—your weekend retreat, a tower seemingly in the middle of nowhere in Georgia. What inspired the design?

My grandparents had a dairy farm in South Alabama, and as a kid I used to climb to the top of the silo and look around the countryside. When I wanted to build my farmhouse, I remembered that silo and the views that you got from up there of a beautiful, but somewhat unremarkable landscape. After doing some research, I concocted the idea of designing a shot tower, which is how they used to make bullets back in the old days. I built very basic floors, and at each level I would get on a ladder and go to the next floor height, look around, and say, “OK, let’s keep going.” When I got to where I could see over the adjacent ridges that’s when I called an end to it. It’s five floors and stands 70 feet.

With no elevator!

No elevator. It keeps me young. Originally the bedrooms were on the second level, which isn’t different from many houses. But ultimately the master bedroom got moved to the third floor, which previously was my boys’ hangout room. It has much better views, a corner fireplace, and light from four sides. Waking up to the sunrise below the tree line is really, really special. I’ll share a poem I wrote about an experience at the farm:

There was a gap in the hedgerow between a persimmon tree and a large cedar, where through cleared bramble and barbed wire, I spotted a large flock of turkeys ambling across the cut over. Surprised by my presence they suddenly flushed, 30 in all sailing down to the bottoms. Now when I cross a gap in the hedgerow my heart beats a little faster, expecting to be rewarded with another flight of birds or, at the very least, a bright flash of memory.

And that pretty much sums up my perspective on the feelings one should have when entering a house or walking through a garden gate: expectancy and excitement.

By Karen Carroll | Photography by Andrew and Gemma Ingalls

Creating Home: Design For Living by Keith Summerour (Rizzoli New York, 2017)