The main house at Weatherstone sits on a platform and boasts a covered and columned verandah that overlooks the parterre garden.

Weatherstone’s three formal gardens reflect my affection for structure and symmetry, and the overlay of sensuality that boxwood can bring to both. But they are also intimately connected to the house’s evolution—and none more so than the parterre along the back of the house, which rose quite literally from the ashes of a great catastrophe: the fire, on January 22, 1999, that very nearly swept the entire place away.

Stately statuary serves as focal points of the parterre garden.

When we first moved into Weatherstone, what existed on that elevation wasn’t all that much. At some point in the twentieth century, someone had tacked on a little screen porch. There were some semi-circular steps that led down to the grass, and a cement walkway. And presiding over it all was a trio of big old maple trees. If this arrangement didn’t subtract from the pleasure of being outdoors, neither did it contribute very much to the experience.

In the years prior to the fire, I visited a number of formal gardens in America and Europe, and discovered that I loved all those straight lines as much as the big flowing herbaceous borders. While I began to apply that kind of thinking to Weatherstone, I couldn’t see myself removing those maples. But the fire compromised them fatally, and then that entire area became a construction site as Weatherstone began its long resurrection. So I had a clean slate, and when my brilliant architect, Allan Greenberg, and I decided to place a long veranda along that side of the house, it offered the opportunity to create a more structured garden experience.

The notion of a parterre—garden “rooms” that form an intermediary zone between the house and grounds—also dovetailed with something the landscape architect Charles Stick, who participated in the garden’s reconstruction, pointed out: that a house as big as Weatherstone needs to sit on a platform. Thus a parterre would satisfy my longing for a Sissinghurst Castle–style garden, and support Weatherstone’s primacy in the context of its surroundings.

An arrangement composed of several variations of tulips clipped from Roehm’s garden makes an elegant addition to a purple-themed table.

The design developed into three communicating realms. The most “serious” part—which expressed the parterre’s traditional geometry of lines, circles, and modified isosceles triangles—abutted the new covered and columned verandah, and corresponded to the house’s living room; a long axis extended through a pair of French doors and across the porch through the center of the parterre to an allée flanked by rows of trees. The second, more relaxed area was set off of Weatherstone’s morning room, and featured a bluestone patio anchored at its four corners by a quartet of linden trees. And the third zone communicated with the kitchen (or dog room, as it has been colonized by canines) and was originally meant to feature herbs and leafy greens, though it evolved in a more floral direction, with iceberg roses, salvia, and the like. The overall arrangement was pretty classic: each space had its own focal point, and maintained clearly defined relationships with the house, the grounds, and one another.

This parterre, the most formal of the three, corresponds to Weatherstone’s great room and serves as a de facto extension of it. Seen here in spring, the boxwood reminds me of a green woolly worm, as it is still too soft to be trimmed. I love the white of the tulips and Sargentina crabapple trees against the green—the two-tone combination is simple, restful, and elegant.

You can make plans. But the garden retains its capacity to surprise, sometimes dashing your hopes and dreams, other times dependably delivering rewards, like my ever hardy and beautiful peonies. Even in a formal design, one learns to take one’s pleasures as they come. In that respect, as in so many others, the garden is a fantastic teacher.

Classical architecture and sculpture characterize the parterre garden, seen here in the fall.

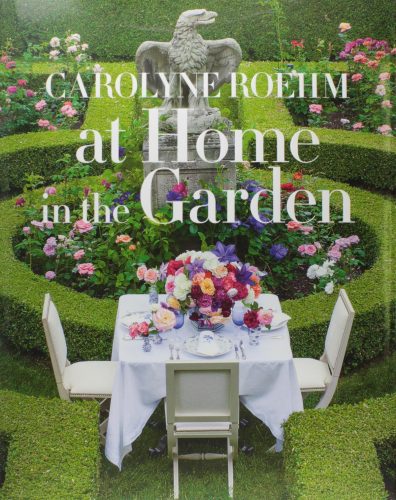

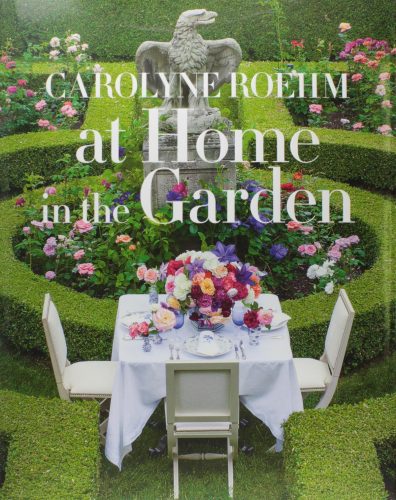

Excerpted from

At Home in the Garden. Copyright © 2015 by Carolyne Roehm. Photographs © 2015 by Carolyne Roehm. Published by Potter Style, an imprint of Penguin Random House, LLC.

More Gardens to Explore

Excerpted from At Home in the Garden. Copyright © 2015 by Carolyne Roehm. Photographs © 2015 by Carolyne Roehm. Published by Potter Style, an imprint of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Excerpted from At Home in the Garden. Copyright © 2015 by Carolyne Roehm. Photographs © 2015 by Carolyne Roehm. Published by Potter Style, an imprint of Penguin Random House, LLC.