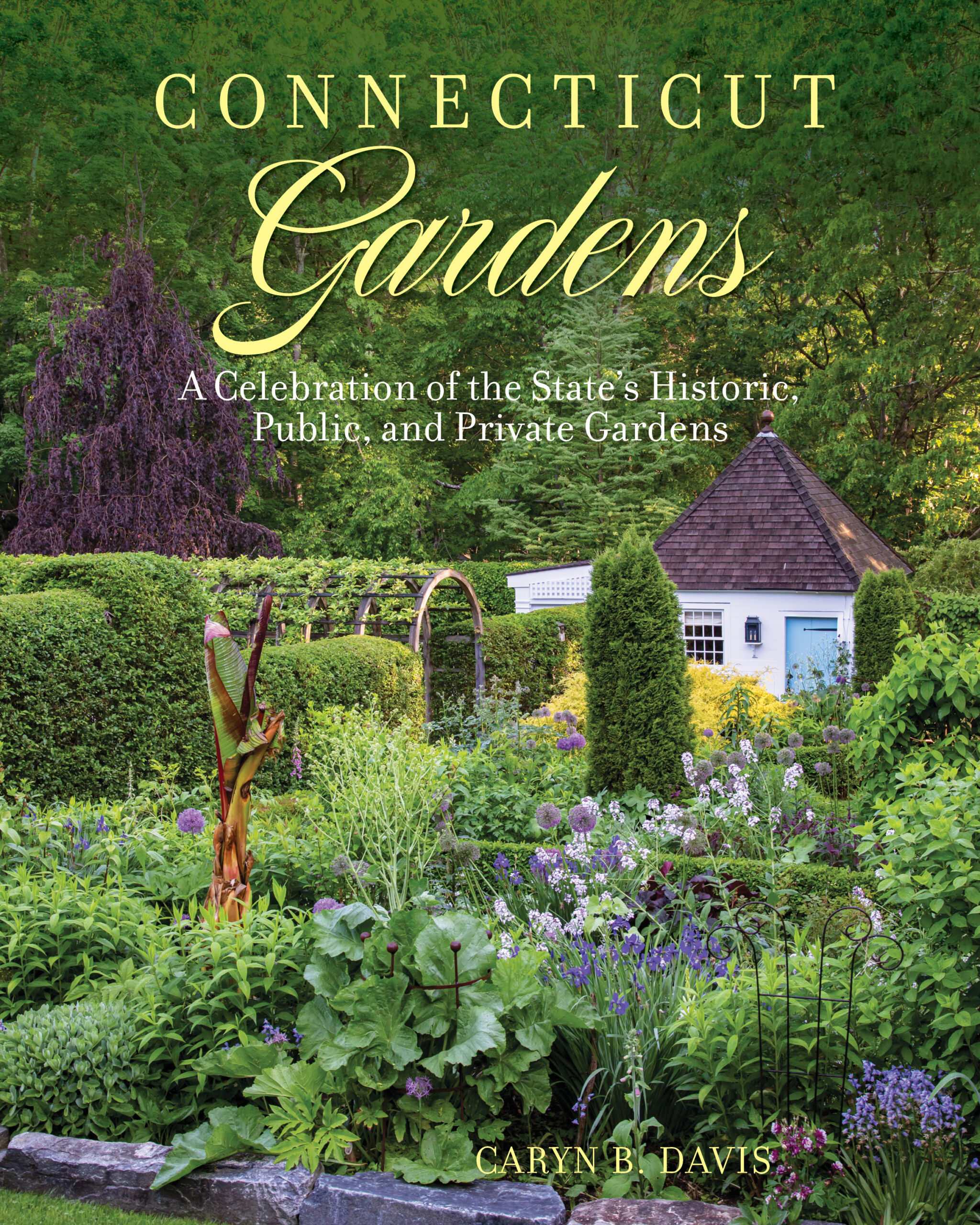

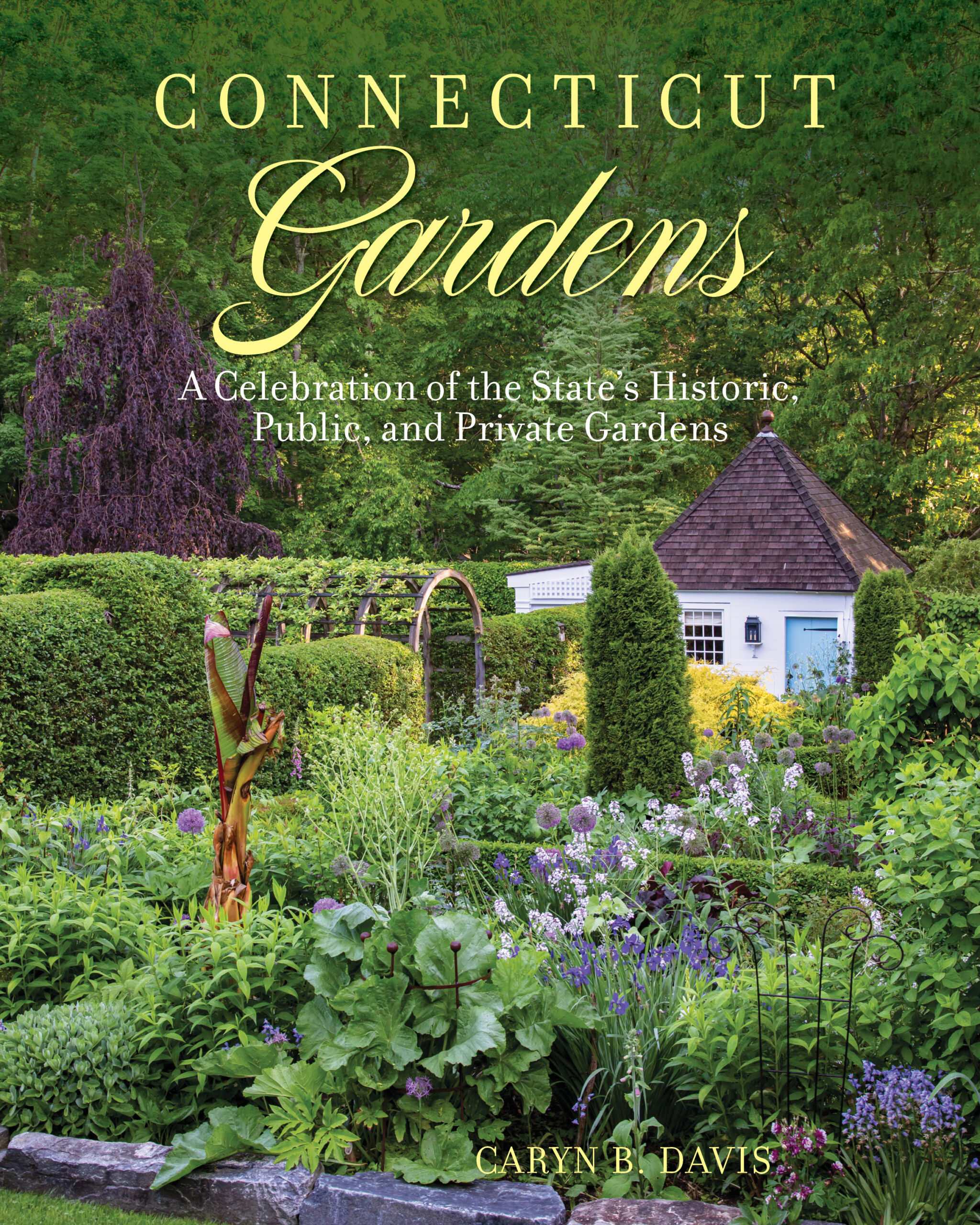

Cover by Caryn B. Davis

Connecticut Gardens: A Celebration of the State’s Historic, Public, and Private Gardens takes readers on a visual tour of some of the state’s most breathtaking historic, public, and private gardens. From simple cottage gardens to stunning botanical achievements and sumptuous formal landscapes, this book introduces readers to the glorious gardens created by passionate amateurs, professional designers, and notable luminaries such as Frederick Law Olmsted, Gertrude Jekyll, and Beatrix Farrand. With lush photography and entertaining yet informative text, Connecticut Gardens is a delight to the senses and serves as a useful guide for discovering new gardens to behold.

HISTORIC GARDENS

ROSELAND COTTAGE, WOODSTOCK

Photo by Caryn B. Davis

In 1833, Henry Bowen left Woodstock for New York City, seeking fame and fortune. He joined the dry goods business of Arthur Tappan, who specialized in imported silks, and ultimately opened his own business. But it wasn’t just the silk trade Bowen learned during this tenure. Tappan was a fervent abolitionist and influenced Bowen’s worldview.

Eventually, Bowen founded The Independent, a pro-abolitionist newspaper. Abraham Lincoln was a subscriber, and at one time, Henry Ward Beecher, brother to Harriet Beecher Stowe, was editor.

Photo by Caryn B. Davis

In 1844, Bowen married Lucy Maria Tappan, daughter of Arthur Tappan’s brother, Lewis, another abolitionist who had won freedom for the captive Africans on the Amistad. The following year Lucy Maria had the first of their 11 children. This prompted Bowen to commission a summer cottage in his hometown.

The Bowens’ bright coral pink, Gothic Revival–style house was designed by renowned architect Joseph Wells and influenced by the tastemaker of the day, Andrew Jackson Downing. Roseland Cottage became the place to entertain. Starting in 1870, the largest Fourth of July celebrations in the United States were held there, and among the luminaries attending were four consecutive sitting U.S. presidents.

Photo by Caryn B. Davis

Though there is no definitive agreement on who designed the gardens at Roseland Cottage, it’s clear Downing’s ideas strongly influenced its landscape. Downing was an esteemed garden designer and horticulturist whom some called the father of American landscape architecture. His popular books on home design established him as a trusted arbiter of Victorian style, and his influencer role and social connections offered a status akin to a celebrity.

An early advocate for the parks movement, Downing believed there was a direct connection between the environment people lived in and their psychological well-being and moral standing. For a devout Congregationalist like Bowen, this resonated. Consequently, there are views of the gardens from almost every window to nourish the soul. Since Downing considered color morally uplifting, bright colors are the norm inside and out.

Photo by Caryn B. Davis

The parterre, with 21 individual flower beds of massed annuals and flowering shrubs bordered by boxwood, is perhaps the most significant feature. Though by definition it’s a formal garden, the layout is organic and curving, having dispensed with the straight lines typically seen in a parterre, for a more relaxed feel.

Following Downing’s guidance, who preferred the English garden style of naturalistic plantings and asserted a country home should have trees, Bowen added hundreds of native and ornamental species to the property.

Exploring this National Historic Landmark gives proof to Downing’s claims that when created with intention and regard for nature, the environments we live in genuinely do nurture our well-being.

PUBLIC GARDENS

ELIZABETH PARK, WEST HARTFORD & HARTFORD

Photo by Caryn B. Davis

When Charles Murray Pond inherited a 33-acre cattle farm in Hartford in 1869, he was already a successful financier and state politician. The following year he did two things that sowed the seeds for his future and our present. First, he married Sarah Elizabeth Aldrich. Second, he asked preeminent landscape architect and Hartford native Frederick Law Olmsted to walk his newly acquired property to determine its suitability as a public park.

Photo by Caryn B. Davis

The Ponds shared a love of the land. Charles pursued his passion for breeding horses, while Elizabeth pursued hers for flowers, using the present-day site of the Helen S. Kaman Rose Garden as a plant nursery for her many gardens.

In 1891, she passed away and when her husband died three years later, he bequeathed the farm, now totaling 90 acres, to the city with the stipulations that it remain a park and be named for his beloved wife.

Photo by Caryn B. Davis

Elizabeth Park officially opened on July 8, 1897. Swiss landscape architect Theodore Wirth designed the grounds while consulting with the distinguished Olmsted firm to blend his formal European style into the otherwise natural landscape. Wirth’s impressive rose parterre opened in 1904, making it America’s first municipal rose garden and the park’s main attraction, although today Elizabeth Park boasts several other spectacular gardens.

Photo by Caryn B. Davis

Despite being the park’s crown jewel, the rose garden was almost plowed under in the 1970s when the city of Hartford encountered fiscal challenges. Fortunately, a group of passionate volunteers formed the Friends of Elizabeth Park (now called the Elizabeth Park Conservancy) and saved this horticultural treasure while making it even grander. Today, the two-acre garden boasts over 15,000 rosebushes in 800 varieties. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, it is the oldest rose garden in the country.

PRIVATE GARDENS

THE GARDEN IN WEST CORNWALL & FARM GARDEN

Photo by Caryn B. Davis

Imagine an old hand-painted wooden sign so weathered by time that its faded letters are barely visible between the rusty nails holding it together. Then ask yourself what makes this sign a treasure to some and trash to others. Next, consider why a homemaker might prefer a contorted piece of bleached driftwood for a centerpiece instead of a beautiful crystal vase of cut flowers. Lastly, why does a worn and faded Oriental rug appear more interesting than a bright new one? The answers are found in the wabi-sabi nature of these things.

Wabi-sabi is the ancient Japanese philosophy of aesthetics that explores our complex relationship with beauty. In essence, it revolves around an appreciation of imperfection and impermanence as qualities that should be revered rather than rejected. Though most Westerners may have never heard of wabi-sabi, many intuitively understand its principles.

Photo by Caryn B. Davis

Gardens can provide a telling visual study of how this Eastern concept of beauty collides and aligns with Western sensibilities. Generally, garden styles rooted in European aesthetics favor order and precision, with hedges clipped into tight rectangular forms and trees chosen for their straight, uniform trunks.

Photo by Caryn B. Davis

By contrast, in an Asian garden, the more twisted and gnarled a tree is, the more it is cherished. Likewise, an asymmetric moss-capped boulder is preferable to an exquisite marble statue of Aphrodite. Sophisticated gardeners appreciate both aesthetics and consciously combine elements of each in their designs. That’s why among these pages, you may see a precisely trimmed boxwood parterre, and at its center sits an ancient-looking urn with a chipped rim and cracked glazing.

Photo by Caryn B. Davis

Michael Trapp is one of the great masters of merging these seemingly opposite aesthetics. Feast your eyes on the images of gardens at his Sharon home or his shop in West Cornwall, and this mastery will be apparent. Of course, as a purveyor of great finds from his international travels, including unique and antique garden accessories, Trapp has an ample selection of interesting objects for his designs. At the same time, the abundance of what might be called his wabi-sabi wares is incidental to his business, and the defining trait that makes his designs exceptional is his creative eye.

Proof of Trapp’s innate skill at blending styles is represented in the images on these pages, but let’s focus on just one: the swing hanging from a limb at his Farm Garden in Sharon. This simple homemade swing has undoubtedly brought joy to its users, but it also doubles as a subtle metaphor for impermanence . . . a child was swinging, and now they are grown. Notice the apparent imperfections of the tree that supports the swing; its asymmetric form and its leafless branches. To some, this tree represents a blight on the landscape, while to others, it possesses a unique character because of its flaws. Now look beyond the crooked tree to the straight lines of the neatly stacked stone wall and the precisely shaped evergreens flanking an opening into the field behind it. Before your eyes are Eastern and Western aesthetics balanced in poetic harmony.

Photo by Caryn B. Davis

By Caryn B. Davis and Chris Lawrie

Photography by Emily Followill

Photography by Caryn B. Davis

Excerpted from Connecticut Gardens: A Celebration of the State’s Historic, Public, and Private Gardens (Globe Pequot 2023)

Buy the book to see more stunning photos of Connecticut Gardens!