Joe-Pye Weed ‘Phantom’ (Eupatorium ‘Phantom’). This native flower is a star of the author’s butterfly garden.

As a landscape architect, I was keenly focused on how to site the house to maximize the views and the light and how to protect the trees during construction. I negotiated with the contractor on how much area he needed to build the house, store supplies, etc. We fenced off all the remaining area to protect the trees and soil from compaction and contamination. And, as it happened, in saving the trees and the original soil, we unknowingly saved the wildflowers too.

Black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa), a popular native herb known for its medicinal applications

Columbine cultivar (Aquilegia canadensis) in spring

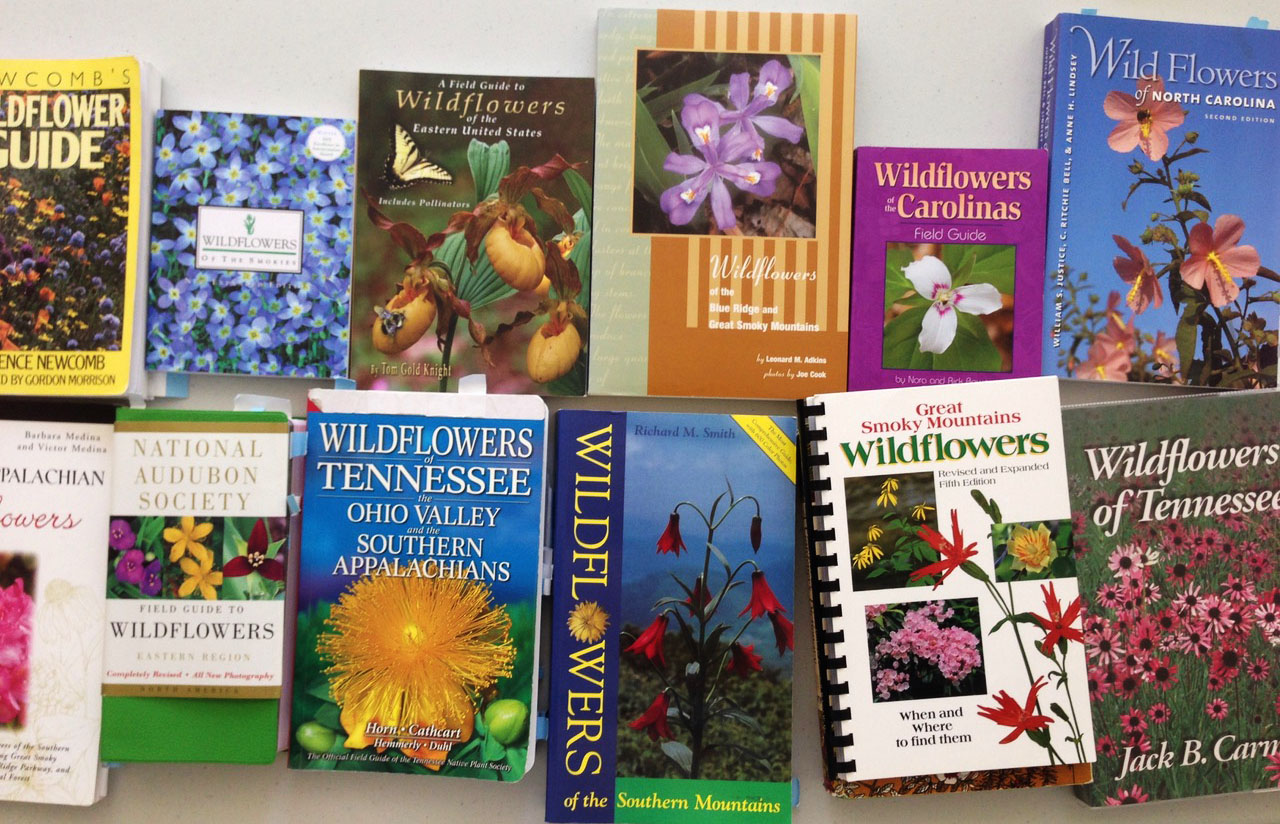

I had already experienced the thrill of discovering unusual flowers on the property and identifying them with a wildflower guidebook. As with everything else in the garden, you don’t know the wildflower until you know its name. Then you can read several different wildflower guides to find out more: how the Cherokees used the plant, how the pioneers used the plant, and sometimes how modern science uses the plant. Every guidebook gives a little additional information that makes it fun to keep reading and learning.

Turk’s Cap Lily (Lilium superbum) merits its name “superb.”

It’s fun to read and learn about wildflowers.

All around me, I see homeowners who buy a wooded lot, scrape off everything in the understory they don’t recognize, and import plants they like from their past gardens, whether it be from California or New York or Texas. What do these plants have to do with the Blue Ridge Mountains in North Carolina? Nothing. Everyone appreciates the views of the mountains and the cool summer temperatures, but what about the authentic spirit of the place, with its authentic native plant palette.

In the fall, butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa) seed pods burst open, dispersing seeds to the wind so that this host to the monarch butterfly may put down roots elsewhere.

Curtis’ Goldenrod (Solidago curtisii) blooms by the author’s front door. The wildflower was saved as a result of careful site protection during construction.

When embarking on a new landscape project, recognizing and preserving what botanical gems we already have requires a shift not only among home gardeners, but also landscape contractors and designers who might suggest clearing out all the “weeds” and understory in order to plant something “nice” purchased from a nursery. And until recently, not many native plants have entered the nursery trade. Fortunately, native plant nurseries and native plant catalogues are gaining popularity now as gardeners discover the benefits of native plants.

Dwarf iris (Iris verna)

Jack-in-the-Pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum) in flower

Jack-in-the-Pulpit in fruit

Every gardener can do something to support the ecosystem, according to Tallamy: If you already have an established home landscape, the next time a tree or shrub dies, replace it with a native. Reclaim a portion of your property for natives by creating a natural area mulched with leaves. Convert a part of your lawn to an informal area mulched with leaves and planted with natives, including wildflowers.

Yellow Lady’s Slipper (Cypripedium calceolus). This native orchid is being extirpated from the wild because unscrupulous people dig it up. Transplanting the orchid this way seldom succeeds because it requires special mychorrhiza in the soil in order to grow.

Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis). Native Americans used the red sap from the roots for body paint.

In addition to supporting the ecosystem, what is the benefit for gardeners? Native plants are low maintenance. Once they are established, native wildflowers and plants require much less water and little or no fertilizer because they naturally grow in the area and are therefore adapted to it. The most important thing is to stop spraying pesticides indiscriminately: Spray only in a limited spot for a specific problem.

Wherever you live in the U.S., you have the opportunity to create in your garden informal areas (large or small), mulched with leaves and planted with native trees, shrubs, and wildflowers. Consult your county extension agent or local wildflower society to find out which wildflowers and plants are native to your area. Select wildflowers that naturally grow in the conditions you have. Trying to grow a wildflower that does not naturally grow in your conditions leads only to disappointment and wasted time and money.

In planting native wildflowers and plants, you are helping the birds, the insects, the ecosystem—and you are helping yourself.

CONTINUE THE WILDFLOWER TOUR

Click the arrows (or swipe if on a mobile device) to see more

Text and photography Mary Walton Upchurch © 2021

Garden writer Mary Walton Upchurch grew up in Montgomery, Alabama, and earned a degree in landscape architecture from the Harvard Graduate School of Design. For more than 30 years, she practiced in Montgomery as an award-winning landscape architect and wrote garden articles for a local publication. Now retired, she lives in western North Carolina where she built a home and garden on top of a mountain with panoramic views of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Follow her on Instagram at @marywaltonupchurch.