Ronni Nicole Robinson with works from a recent collection called Pretty In Pink, featuring tulip magnolias

Flower Q&A:

It’s a pleasure to talk to you. We’re big fans of your art [which sells under the name Ron Nicole]. Tell us about your background.

Ronni Robinson: I’ve always been obsessed with flowers. Growing up in Philly, I remember noticing the flowers that grew through the cracks of the concrete. I would stop to admire them, then fall behind and usually get into trouble. Later as an adult, I kept working with flowers, trying different things. To make money, I worked in the restaurant industry, working 80-hour weeks, but thought, This can’t be it. I knew I wanted to work with flowers, but I wasn’t exactly sure what I wanted to do.

Was there a clarifying moment?

About three years ago, I was visiting the Barnes collection and saw a big metal relief hanging in a gallery. When I looked closely, in the far corner I saw this tiny little flower in relief. That inspired me to start working with flowers in clay and plaster.

Two of Robinson’s first pieces still hold prime position in her studio.

All of your collections sell out. Have you been surprised by the popularity of your work?

I’m indebted to people like Alison Hangen, a woman I met working in restaurants. She knew many aspiring artists working in the hospitality business, so she started a group called Arts in the Industry and organized a show in October of 2016 where she encouraged me to exhibit my work. I thought, This is going to be so embarrassing, but my pieces sold out. I thought, OK, I guess I should try making this a business.

I learned quickly that you can’t be an artist by yourself. You need the help of your community. I also learned that you don’t have to have everything figured out all at once.

Tell us how you go about making a new piece.

I start with clay. I spend a few hours just massaging it, so that it’s soft but firm. That’s my favorite part; it’s when I clear my head. After it’s very smooth, I’ll touch a flower to see how it presses inside. I lay the flowers out first to see how they’re going to be pressed—you have to see it in reverse. Then I press the flowers in the clay. Once I get a flower out, I frame the clay with a wood frame and fill the outer edges in concrete and use my color mix.

Robinson with a bouquet ready to take back to her studio.

This sounds very Zen but also tedious! How long does it take to remove the flowers from the clay?

It took a lot of broken pieces and a lot of disappointment in the beginning, but you have to do the trial and error to develop. The hardest part is getting the flowers out. Something like Queen Anne’s lace can take me a week to remove. Needless to say, I have great tweezers.

Any favorite flowers you love to work with?

I like delicate, whimsical ones that have little stems that you can flex around. I love cosmos and anemones. And although the Queen Anne’s lace gives me such a hard time, it’s one of the prettiest flowers to press.

You’ve written that you want your pieces to give people permission to slow down. Talk about what you mean.

I don’t want my pieces to be statement pieces. The goal is for the art to be in the background, for you to live with it, hang out with it. And when you catch a glimpse of it in your daily life, it allows you permission to slow down, to notice the details.

Robinson puts the finishing touches on a larger work.

What’s on the horizon for you?

Well, it’s funny you should ask that. My husband and I have been trying to get this farm in Quaker country outside of Philly, and right before you and I got on the phone, he called to say we got it! So you’re the first person to know that in May we’re moving from our little one-bedroom apartment in Philly to a farm.

That’s so exciting! What does this mean for your art?

It means I’ll be able to work the way I’ve always wanted to work. I’ve become an expert at keeping stem flowers alive, but having my own garden—which I’ve never had before—will completely change my work.

More from Ronni Robinson’s Studio

Click the arrows (or swipe if on a mobile device) to see more

Ronni has been working on her largest collection plaster pieces to date, “Wall Candy 2022.” The exhibition opens on October 7, 2022 at the LAA Art Collective in New Hope, Pennsylvania.By Kirk Reed Forrester | Photography by Amy Franz | Art by Ronni Robinson, ronnicole.com

By Kirk Reed Forrester | Photography by Amy Franz | Art by Ronni Robinson, ronnicole.com

Originally published May 2019. Updated October 2022.

ARTIST UPDATE

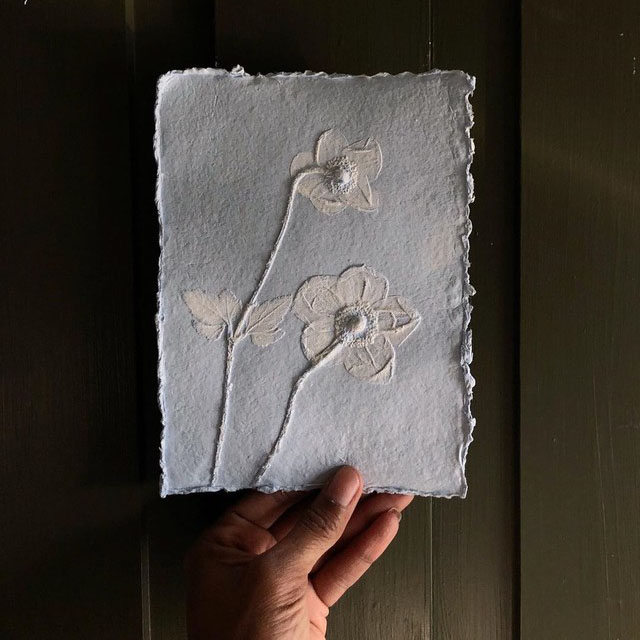

Since we last chatted with Ronni in 2019, she has added floral paper reliefs to the Ron Nicole line. She handcrafts each piece using her own paper recipe, which she casts in the same molds as her plaster originals. She also shared with us her husband’s recipe for The Violet Beauregarde—a refreshing cocktail made using leftover blueberries harvested for her art.