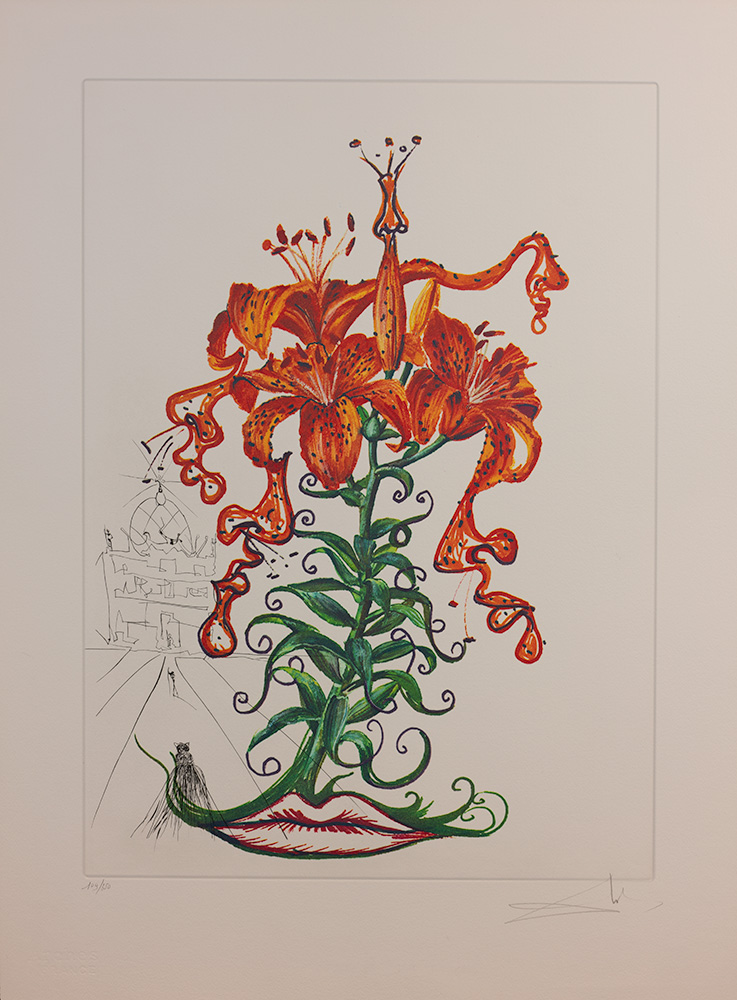

Floral motifs have been a mainstay throughout Liberty’s 140-plus-year history. ‘Constantia,’ a late 19th-century Art Nouveau print with curvaceous stems, enjoyed renewed popularity in 1961. Photo courtesy of “Liberty & Co. in the Fifties and Sixties” by Anna Buruma (ACC Editions, 2008)

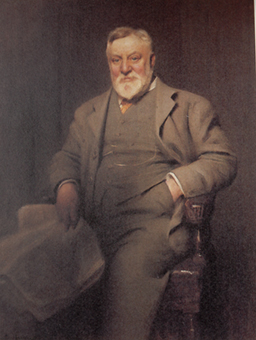

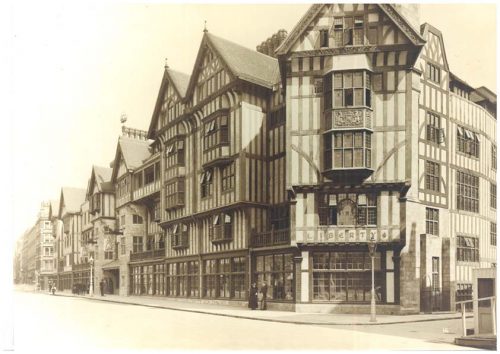

His name is synonymous with artfully printed fabrics—everything from dense little florals in watercolor hues to large, undulating botanicals in rather psychedelic shades. For over 140 years, these prints have attracted admirers from literary legends to fashion royalty to First Ladies. But Arthur Lasenby Liberty was not a designer. Instead, the founder of London’s iconic store housed in the big mock-Tudor building on Great Marlborough Street was a brilliant retailer with a keen eye for beautiful textiles.

Arthur Lasenby Liberty. Portrait by Arthur Hacker

“What Arthur Liberty had was an incredible knack for finding talent,” says Martin Wood, author of the book Liberty Style (Frances Lincoln, 2014). “Liberty not only knew the market, he also pushed the market in new directions.”

The relationships Mr. Liberty had with artists and designers, and his store’s connection with creative people, have endured nearly a century after his death. In 2015, the exhibition Liberty in Fashion at London’s Fashion and Textile Museum celebrated this fact with a display of some 150 textiles and clothes featuring botanically based prints—the beloved, riotous paisleys and English garden florals. But before flowers became inexorably linked to Liberty, it was color that enticed customers.

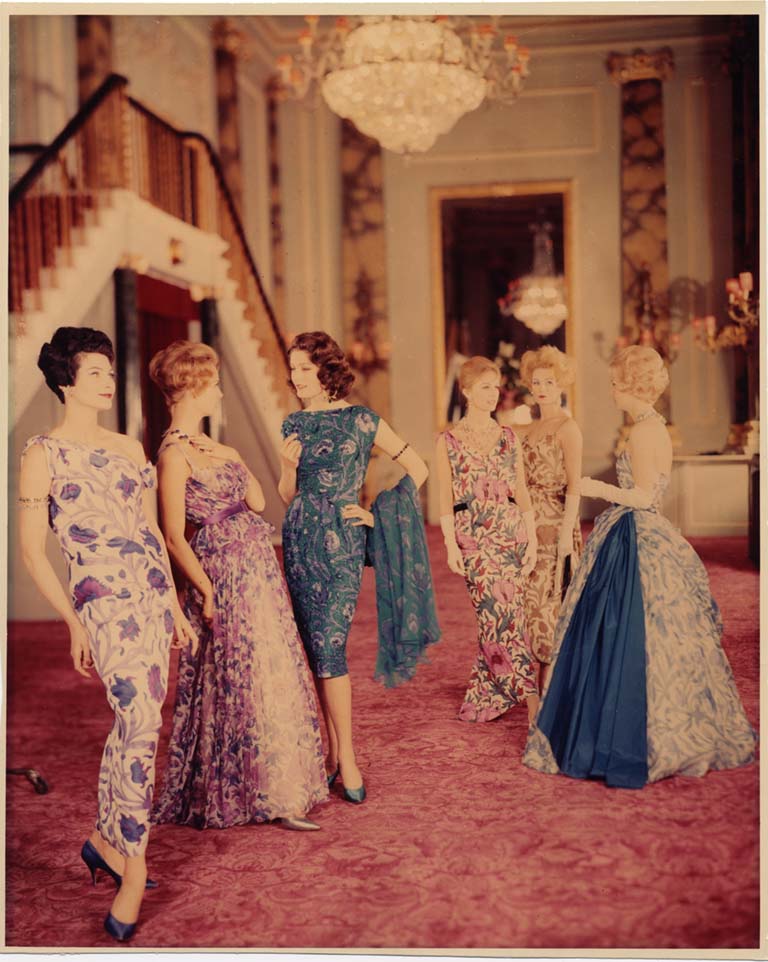

Liberty’s Lotus collection of fabrics shown circa 1960 in the Crush Room of the Royal Opera House. Photo courtesy of Liberty & Co.

For Liberty, the cloth connection began with soft, flowing, vegetable-dyed Asian silks. The rich yet nuanced colors of these imports, which served as the foundation of Liberty’s first small shop on London’s Regent Street in 1875, were extremely important and “really put him on the map,” says the company’s archivist, Anna Buruma. A world apart from the stiff European fabrics sold elsewhere, these fluid silks were perfectly suited to the looser frocks favored by artsier Victorian women. In fact, Oscar Wilde would ultimately quip, “Liberty is the chosen resort of the artistic shopper.”

Before long, Liberty began collaborating with British makers to produce his own printed silks and cottons. Teaming with Thomas Wardle, an Indophile and one of Britain’s premier dyers and textile manufacturers, he created Asian-inspired florals rendered in distinctive colorways specific to Liberty.

The Tudor-style Liberty store built in 1924 remains an icon on Great Marlborough Street today. Sadly its founder, Arthur Lasenby Liberty, did not live to see its completion. Photo courtesy of Westminster City Archives & Liberty Ltd.

Although many of the surface patterns were done by anonymous designers, some well-known talents can be identified. For example, Wood cites Charles Voysey, a major designer of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, whose fabrics and wallpapers tend to be botanically based but frequently include animals, too.

“Voysey’s florals are never oppressive. His backgrounds allow for more breathing room,” Wood says, adding that Voysey’s flowers still resonate today. Also shaping the Liberty look were the Art Nouveau florals of Harry Napper, an employee of the Silver Studio design firm that produced designs for the store. Flattened poppies and other highly stylized blossoms recurred in Napper’s furnishing fabrics. Indeed Liberty became so closely linked with Art Nouveau that Italians started referring to the overall artistic movement as Stile Liberty.

Today, Liberty’s in-house design studio continues to draw upon these early patterns for inspiration. Case in point: printed cotton Jugendstil, partly based on a leafy 1890s Silver Studio design with intertwined vines and large rounded blossoms.

Arnold Scaasi’s dress designed with Liberty’s ‘Eustacia’ from 1960. Photo courtesy of “Liberty & Co. in the Fifties and Sixties” by Anna Buruma (ACC Editions, 2008)

Of course, fashion is cyclical, and Art Nouveau’s curves haven’t been perpetually in vogue. Thus by the 1920s, the store introduced silk scarves to function as foil for a greater variety of designs that ranged from geometrics to novelty prints to historically inspired florals. (Decades later, Jackie O would have pillows made from her collection of Liberty scarves.)

The 1930s saw more conservative, small-scale sprigged florals added to the fabric range, typically printed on Tana Lawn—a fine spun cotton named after Lake Tana in Ethiopia where the fibers were found and thought to be exceptional enough for the young British princesses Elizabeth and Margaret. So popular were these prints that ultimately the term Tana Lawn became synonymous with allover florals rather than the cloth itself.

From advertisements to magazine pages to runways, Liberty florals blossomed everywhere in the ’60s and ’70s, as seen in this cover for French Elle. Image via Elle France/Scoop

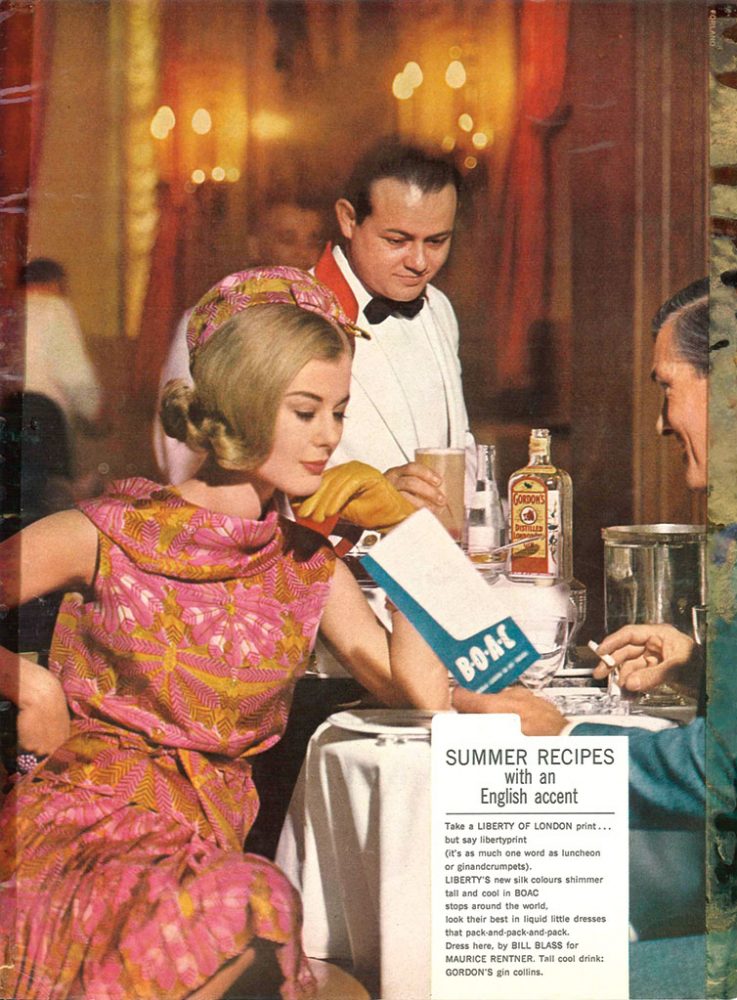

An advertisement for Bill Blass and Gordon’s Gin showing Liberty’s ‘Radames’ print from 1961. Courtesy of “Liberty & Co. in the Fifties and Sixties” by Anna Buruma (ACC Editions, 2008)

After World War II, Liberty began hiring designers to work in-house. In a sort of Liberty-meets-midcentury-modern vein, Althea McNish and Colleen Farr worked to invigorate the dress fabric collection with abstracted florals and geometrics. But as the Swinging ’60s were about to dawn, organic Art Nouveau florals seemed ready for rediscovery and Liberty was poised for a true renaissance. The store released the Lotus collection, an assortment of circa 1890s poppy- and rose-filled florals, some of which were attributed to Napper. The designs weren’t altered but in some cases the colorways were punched up.

French fashion icon and singer Françoise Hardy was photographed in 1970 wearing Yves Saint Laurent’s wool challis midi dress made with a Liberty floral. Photo © Condé Nast Archive/Corbis

Later, Bernard Nevill, perhaps Liberty’s most high-profile in-house designer, came on board to rev up the Lotus line with new designs, like large Matisse-inspired florals and paisleys. Couturiers began snatching these up virtually before the dye had dried, with Yves Saint Laurent’s use of the prints for his then-groundbreaking midi and maxi dresses garnering worldwide attention.

By the end of the ’60s, Liberty florals had become firmly—and permanently—entrenched in pop culture. Jackets made with patterns that were perhaps previously better suited to sofas in Victorian and Edwardian drawing rooms were being sold to rockers such as George Harrison by the Kings Road boutique appropriately named Granny Takes a Trip. The masses of Tana Lawn that French fashion house Cacharel used to create blouses and bohemian dresses carried the Liberty wave right into the ’70s, and it’s been riding high ever since. Today, on the more tailored end of the spectrum, stateside retailers Sid and Ann Mashburn are currently known for sprinkling their classic, clean-lined shirts, dresses, shorts, and ties with bits of the Liberty magic.

Liberty’s florals through the years

Click the arrows (or swipe if on a mobile device) to see more

But given that the Liberty range has never been restricted to botanical motifs, why is it the floral prints that have become so closely associated with the venerable store? Buruma says she can offer no scholarly proof, only her personal theory about the phenomenon:

“Flowers have long been a popular English theme, even going back to the 16th century when women were choosing to wear floral prints,” she says. Yes, it’s undeniable that the British have had a long love affair with gardens, with flower arranging, and, of course, with their beloved Liberty. Thus it should come as no surprise that the emporium’s botanical prints and patterns are happily destined (and designed) to stand the test of time.

By Courtney Barnes | Originally published in Flower Magazine, September/October 2015

Basil, Mint & Thyme Bar Soap by Liberty London

Editor Favorite

On a recent trip to London for the 2019 Royal Horticulture Society Chelsea Flower Show, Flower‘s Editor-in-Chief Margot Shaw stopped by Liberty on Regent Street to stock up on bars of this deliciously scented Basil, Mint & Thyme soap to bring back to the staff (much to everyone’s delight). Source: libertylondon.com