An antique French fountain, surrounded by Australian tree ferns in clay pots, provides a resting spot for one of Gatewood’s several peacocks that roam the grounds. Photo by Rodney Collins, courtesy of Rizzoli

Furlow Gatewood is as unreflective about how, exactly, he laid out the 11 acres on which his houses sit as he is about the rest of his magical creations. “It just happened,” he says. Also, like a lot of Southerners of his generation, he is firm about the fact that the property is a “yard” rather than a “garden.”

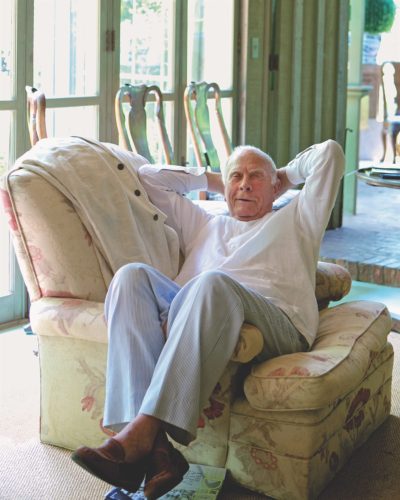

Gatewood relaxes on the back porch of the Barn, one of four structures on his property. Photo by Rodney Collins, courtesy of Rizzoli

He has a point on both fronts. There was never a long-term, drawn-up landscaping plan—the grounds evolved as the number of houses and outbuildings grew. And though there are dozens of plant varieties, including concentrations of more than 1,000 daffodil and narcissus bulbs and masses of white butterfly ginger lilies, there are no gardens in the proper sense. As he did everywhere else, Furlow relied on his remarkable sense of proportion. More important, he simply planted what he loves.

Since the property itself is on part of what used to be his family’s farm, there are still the majestic remnants of the pecan groves, once so common in the area. An existing allée of the trees was made far more dramatic with underplantings of dozens of crape myrtle bushes and another “allée” of 26 hydrangeas in clay pots. The rest of the plant material is similarly Southern: enormous oaks in which the peacocks roost at night; pear trees and old-fashioned “sugar” figs; azaleas and old roses; and camellias, including Furlow’s two favorites, the ‘Queen Bee’ and the ‘Frank Houser,’ a hybrid that originated in Macon, Georgia.

A peacock perches on the gate outside of the building appropriately named the Peacock House, which used to be a winter plant repository before it was outfitted with a bedroom, bathroom, and kitchen. Photo by Rodney Collins, courtesy of Rizzoli

Three of the outbuildings are especially typical of Southern homes of a more gracious era: a pair of pigeonniers, or pigeon houses, which in this case contain garden tools and architectural fragments; and a chicken house, which currently serves as a hospital for injured peacocks. The pigeonniers came into being a few years ago after Furlow found a pair of fanlights he loved and promptly designed two structures around them. The chicken house, also of Furlow’s design, was once home to 50 Japanese Bantam chickens, a mostly ornamental and notably amiable breed that has graced aristocratic Japanese gardens for more than 350 years. They were ensconced in Furlow’s own place for a little over two—until, he says, he “got bored with them” and gave them away.

The peacocks are unlikely to meet a similar fate. About a decade or so ago, Furlow became enchanted by a pair kept by his nephew, Jimbo Gatewood, who lives in his mother’s former house next door. “That got me started,” he says, and since then he’s acquired an ever-growing brood that now numbers more than 40. That’s a lot of birds, but it is precisely this kind of volume—of birds, of plants, of charming garden ornaments and outbuildings—that makes the “yard” so special. “I think Furlow lives for interesting scale,” says decorative painter Bob Christian. “When most people would put in 6 hydrangeas, he will put in 40. Or he’ll say, ‘Let’s go put in 600 bulbs this afternoon.’”

Twenty-six potted hydrangeas line the driveway and greet guests as they head toward Furlow Gatewood’s complex in Americus, Georgia. Photo by Rodney Collins, courtesy of Rizzoli

No matter what he adds, the components are invariably harmonious. It helps that there are so many mature boxwoods available for transplanting in front of the more recently added structures and that most of the buildings are of the same regional vernacular. “He is not trying to do Williamsburg down there,” says Bob. “Everything looks like it should be exactly where it is. And that it has been there forever.”

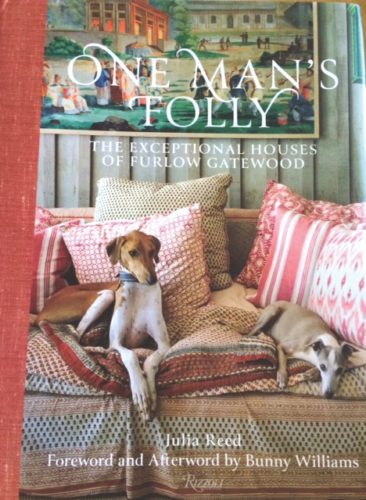

Excerpt reprinted from ©One Man’s Folly: The Exceptional Houses of Furlow Gatewood by Julia Reed (Rizzoli New York, 2014). Photos by Rodney Collins, Courtesy of Rizzoli.

Excerpt reprinted from ©One Man’s Folly: The Exceptional Houses of Furlow Gatewood by Julia Reed (Rizzoli New York, 2014). Photos by Rodney Collins, Courtesy of Rizzoli.