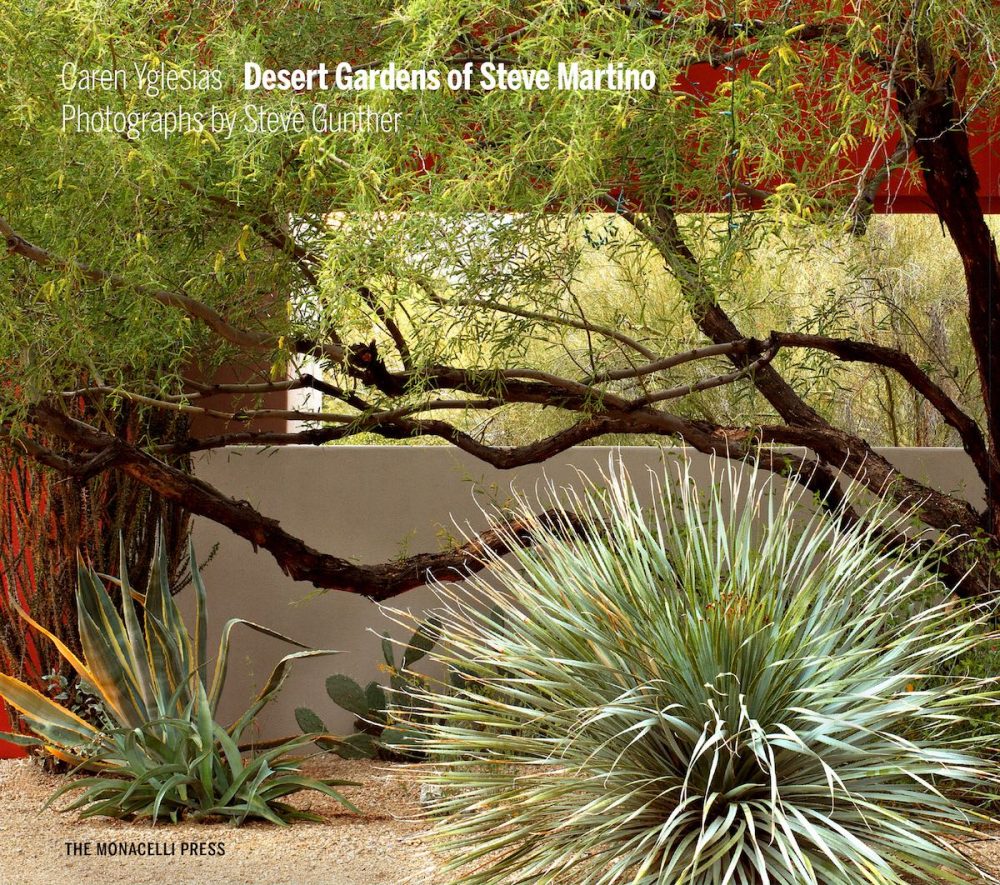

Steve Martino designs desert gardens that capitalize on native plants, rather than fight them. Here, our associate editor finds out more about his approach.

Kirk Reed Forrester: Congratulations on your new book [Desert Gardens of Steve Martino, Monacelli Press, 2018]. Steve Martino: I’m still shocked it got done. It only took three years. But I just got back from Costco and I saw it there, right next to the books on how to cook spaghetti.

In the book, you describe the evolving attitude toward the desert landscape, a place “historically viewed as a wasteland where anything done to it was an improvement.” Why have people had such a hard time embracing the desert aesthetic? I think to some, the West is seen as a place to extract resources, as a place to mine, whether it’s water or whatever. There wasn’t a value placed on the landscape. There have always been developers who recklessly promote their fantasies to make this place look like something else and landscape architects who accommodate their vision.

You must have bumped up against this philosophy frequently when you began your career. I remember one of my first jobs was working for an architecture firm on a town house in Phoenix. We were using all the common Mediterranean plants popular at the time, none of which were native and all of which were going to require a great deal of water. I noticed that the vacant lot next door had desert plants growing like crazy with no irrigation at all, and thought, “What’s wrong with this picture?” I asked the head architect, “How come we don’t use these plants that are growing on their own?” He said, “Oh, those are weeds.” Relying on native plants was really difficult in the beginning of my career, but it seemed right. I like to say after 20 years, I was an overnight success.

When you were starting your career, you had a hard time finding native plant species in Phoenix nurseries, so you backpacked around Arizona and northern Mexico with a horticulturalist to gather seeds. Can you talk about those trips? The horticulturalist, a man named Ron Gass, has an encyclopedic knowledge when it comes to plants of the Sonoran Desert. We’d go out and collect seeds in our backpacks; then he’d come back and try to grow them, and I’d use them in my designs. Ron continues to be my secret weapon.

It must have been gratifying to be able to source native plants for your own projects. I originally used native plants just for their looks. Then I noticed that they bring along an entourage—pollinators, predators—and suddenly the garden becomes a habitat. Seeing that got me hooked on desert plants, and my mission became bringing them back into the city.

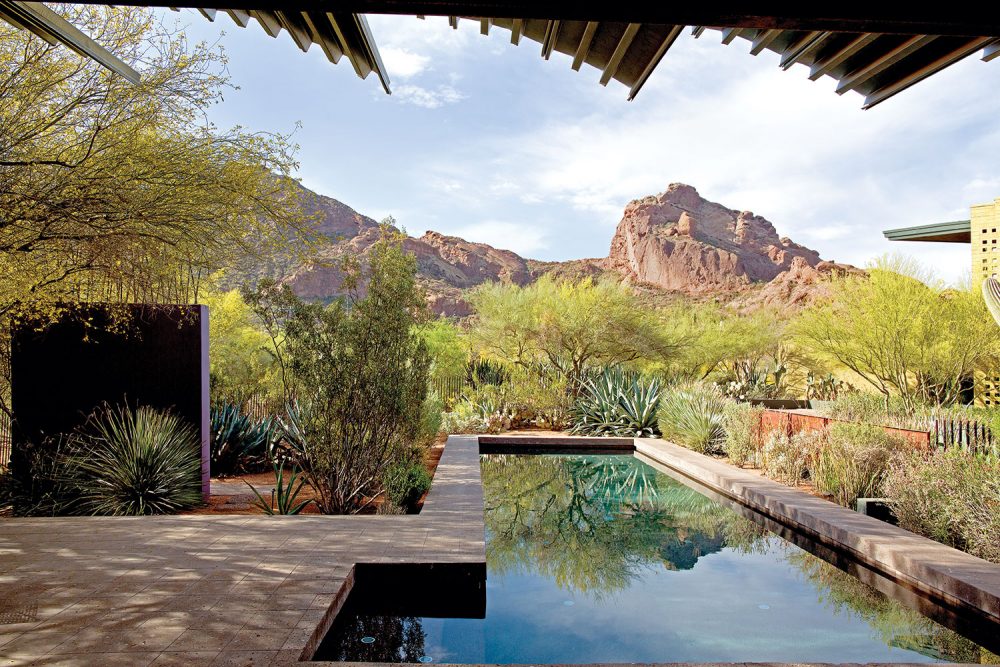

Looking at your work, I’m struck by the way the desert landscape strips things down to essentials: sun, shadow, water, shape, color, texture. Each component seems magnified, which makes me think that editing must be crucial to your work. A basic garden unit is a wall, a tree, a chair, and a little water. If you don’t have that, you don’t have a garden. If you want a bigger garden, add more trees, add more chairs. The model I really like is these Portuguese farmhouses that are turned into gardens. They’re so simple and perfect—just an olive tree, a wall and a chair. I want to create that in my climate— things that look like they belong.

Any landscape architect in the desert has to contend with the sun. You write that you think of it as another building material. What do you mean by that? I use the sun like a sundial, so we can program shadows and make it part of the design. That’s one reason I love cactus— they make their own shadow.

You advise your clients to “kill the lawn and save your grandchildren.” Does that mantra resonate? Most people I work with get it. Think about it this way: It’s taken native plants a million years to get it right. Why fight it?

Deserts can be punishing places. Do you ever have environmental envy and wish you could design for the Hawaiian tropics, the Bavarian forest, or the Tuscan countryside? I think forests are creepy. My wife is from Missouri, and you get ticks on you in the forest. I’m used to growing up here, where you see the rocks and the mountains. I like to see the rocks. Plus, I have a friend who’s a landscape architect in Miami, and he seems to share most of the general frustrations I have.

So, I take it you’ll stay put? I love the desert. I’m a solar-powered person.

By Kirk Reed Forrester | Photographed by Steve Gunther

Desert Gardens of Steve Martino, Monacelli Press, 2018