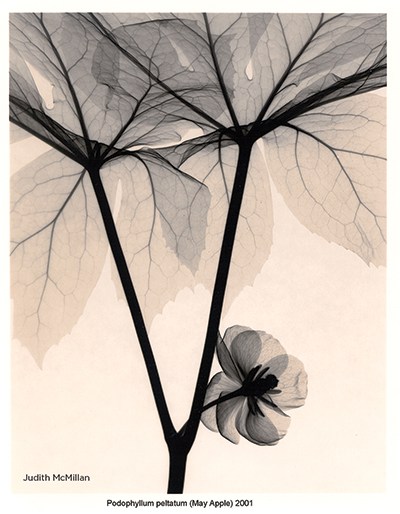

Flowers have been a natural part of artistic expression since the beginning of time, but when art and technology combine to create an X-ray print, it encourages us to look beneath the surface—or rather peer within—and see a lily, a tulip, a leaf, or a rose in a whole new light. “I believe we’re all gardeners at heart,” says British artist Hugh Turvey, “and flowers are inherently beautiful. But the X-ray connects and keys people into their own imaginations.” Floral X-rays focus on the dense internal structure of the plant and let the usual stars of the show—the colorful petals and foliage—fade into transparency. Instead, the “bones” of the flower are revealed, stripping away details that distract from the essence of the subject.

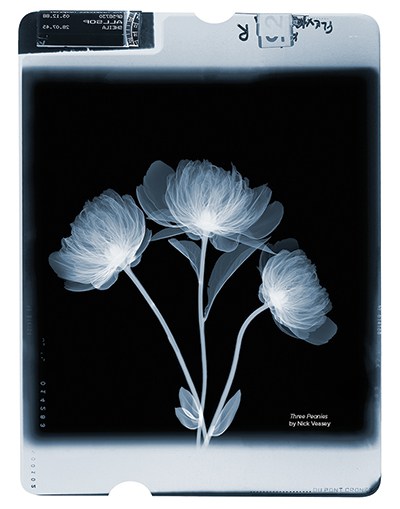

X-ray images are a relatively new discovery, having transformed the world of science and medicine a little over a century ago. However, as their initial focus on anatomy broadened, an art form was also born. Today contemporary artists and scientists continue to exercise their creative muscles, marrying an ever-evolving technology with their artistic perspectives. They create compositions and play with distance, sometimes focusing on just the blossom or on several flowers together. Artist Nick Veasey says, “I position the subject and I see how it looks, but to take the X-ray I have to leave the room, close a huge, heavy door, and wait for two to three minutes,” he says, referring to the process that protects him from overexposure to the radioactivity. “Sometimes it works, but sometimes it doesn’t. Something might move and destroy the composition, and I do it again.”

Although the process (and, of course, creative outcome) differs depending on the artist and the machine used, it always involves patience and a methodical approach to an organic—and often quickly wilting—object. Yet all start with the same “tools”: an X-ray taken in an enclosed space, behind a reinforced lead door. The reality of radioactivity is never far from the artists’ minds (and precautions are taken just as seriously as the art), but it doesn’t distract from the task at hand. “People worry about the radiation, but we are all exposed to small amounts of radiation regularly,” says Turvey, “whether we’re flying at a high altitude or going through security at the airport, and we’re fine.”

Printing the image brings in another layer of complexity, as the paper chosen is part of the artistic process. An emulsion may be applied, or coloration may be added to enhance the ethereal impression of the work. New York photographer Bryan Whitney says, “I hand color all of my work, essentially brushing it in with the computer. I’m trying to get the right tonality.” By “right tonality,” Whitney is not describing the exact reproduction of an image. Instead he works with the flower and the medium to convey his impression of the subject. Inspired by the idea of transparency, Whitney’s colorations reveal the density of the flower—more opaque color at the dense stem, and faint shading at the petals to reflect the thinness of the blossom.

With X-rayed botanicals, artists transcend the outwardly beautiful by deconstructing the physical to get to the heart of a flower. To look at a skeletal image of a chrysanthemum or magnolia is to realize that the phrase “beauty is only skin deep” may apply to the human world but not the botanical one.