Constance Spry, the legendary British floral designer, is enjoying a renaissance in the public imagination. It’s not just that her democratic vision of flowers allowed even the lowly cow parsley and cabbage into the spotlight, but her fascinating life and unconventional ways seem so fitting for our times. Keen to shun the prim opulence and restrictive rules of Victorian-era flower arranging, Spry forever changed the way we look at flowers as design elements—and hoped to inspire both aristocrats and commoners alike to embrace the simple beauty and romantic charm of nature’s most glorious creations.

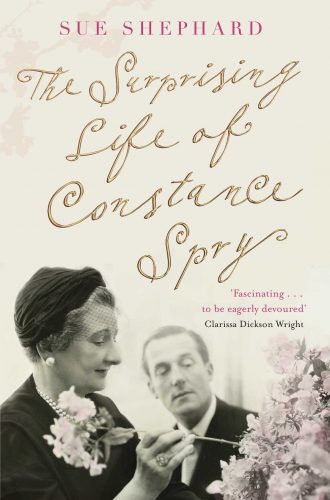

Sue Shephard, author of the biography, The Surprising Life of Constance Spry (Macmillan, 2010), has undoubtedly fueled the fire for all things Spry. An engaging story that spans Spry’s life, from her gritty beginnings as a schoolteacher’s daughter in turn-of-the-century Ireland all the way to her magnificent floral creations for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, the book is a fascinating look at an unlikely success story—that of a woman who consistently discovered the beauty in unexpected places while she herself also defied convention. She became an icon, even a beacon, for generations of women attracted to her ingenuity, style, charm, and thrift.

So who is this visionary, the “flower decorator,” as she liked to be called? It might surprise some to learn that she is the namesake for the very first English rose cultivated in 1961 by now-renowned grower David Austin. The ‘Constance Spry’ rose, a glorious, pink confection, gives off a heady scent of myrrh and thrives as either a hardy shrub or a vigorous climber. Likewise, Connie, as she was known to her friends, was adaptable. Born in Derby, England, in 1886 and raised in Ireland, she found refuge from her domineering mother in the gardens of her childhood, where she began to take note of what would become her favorites: old garden roses, lilac, mock orange, laurel, buddleia, and evening primrose, as well as grasses, weeds, and other typically overlooked plants and materials.

Though flowers and gardening would be her lifelong passions, under her father’s direction she began her early professional life as an educator and social reformer. Traveling by horse-drawn wagon through the Irish countryside, she became a proponent of healthy living, educating housewives on the benefits of fresh air and nutritious food as part of a “War on Consumption” campaign. After a disappointing marriage to a coal mine manager, she took her only son back to England to begin life anew. It was there she met and fell in love with Shav Spry, a colonial civil servant who would be her lifelong companion.

It wasn’t until the age of 41, after a successful career as a headmistress, that Spry’s amateur talents as a floral designer were noticed by an influential lunch companion, leading her to Norman Wilkinson, a theater designer and kindred spirit whose encouragement would launch her meteoric design career. With a commission to do flowers for cinemas and a perfume shop, Spry took her unorthodox visions of gathered materials and artful references out of the homes of friends and into the public eye, where she was lauded for displays that in an incredibly modern twist included leaves, berries, seedheads, wild clematis, and golden hops mixed with exotic orchids. Her fate was sealed.

Suddenly this middle-aged woman found herself thrust into the social scene, befriending legendary decorator and fellow entrepreneur Syrie Maugham and an exuberant crowd of theatrical personalities and social luminaries. Her highly sought-after and fashionable business, Flower Decorations Ltd., thrived, continually adding new hands to help satisfy demand. A floral design school, books, and even a residential school of the home arts followed.

In 1937, Spry was called upon to arrange the flowers for the controversial wedding of Wallis Simpson and the Duke of Windsor. And she was asked to not only design the flowers for Queen Elizabeth II’s 1953 coronation, but also to enlist her collaborator Rosemary Hume and the students at the Winkfield Place residential school to create and serve the luncheon that followed, defined at least in part by plates of Hume’s soon-to-be-famous Coronation Chicken. The flowers, many donated from private homes and shipped in from members of the British Commonwealth, included lilies, roses, carnations, sweet peas, gladioli, peonies, delphinium, lotuses, frangipanis, and protea. The scale of the pageantry and the tight timeline involved in processing and arranging such a mass of ephemeral beauties was a huge challenge, and one that Spry and her staff met without reserve.

Despite the fanfare and fame that Spry enjoyed, she was always at heart an educator. She encouraged the women of her shop, as well as her many pupils, friends, and readers, to learn firsthand the joys of cultivating beauty in all its forms.

If one of the defining characteristics of a trailblazer is the ability to disseminate a singular vision to the masses, the seeds Spry planted have certainly been hardy and will continue to bear fruit for years to come. The design philosophies she espoused feel thoroughly fresh and contemporary to many of today’s leading floral designers. The young but already celebrated Emily Thompson—a sculptor-turned-floral designer in Brooklyn who creates elegant, artful arrangements of romantic flowers, wild vines, fruits, and foraged materials—is often mentioned in the same breath as Spry. “I feel her influence on me and my compatriots in our love and respect for dragging the out-of-doors in and our attempts to bring living materials, in all their mess and complexity or stylistic associations, into relief,” Thompson says. “I love her work, her range, her inventive, personal approach, and her sense of the character of each material.”

For Spry, always an arbiter of taste and a keen enthusiast of elegance and grace, the complexities and messes and her unprejudiced eye were perhaps the secrets to her not-so-secret success. We owe her a great debt for her many contributions to the decorative world at large: for the old garden roses she collected and saved from the ravages of World War II; for the appreciation of floral design as an art form; for the enthusiasm and confidence she instilled in young beginners; and for the simple yet sophisticated idea that with the right attitude, uncommon beauty can be cultivated from surprisingly common materials.

Sue Shephard’s biography, The Surprising Life of Constance Spry, illuminates the many adventures of a woman who led an extraordinary life.